Shankaracharya

Gallery | Links:

As the dawn of the medieval era unfurled approximately 1,500 years ago, India stood on the precipice of losing its esteemed Vedic heritage. The Vedas, once the cornerstone of spiritual wisdom, had been relegated to mere ritualistic practices aimed at fulfilling earthly desires. The culture had begun to exclusively practice the Karma Kanda (the section of the Vedas that deals with rituals, ceremonies, and sacrifices. The term “Karma” in this context refers to action, specifically ritual action) and neglect the Jnana Kanda (often synonymous with Vedanta, which refers to the portion of the Vedas that deals with knowledge, particularly spiritual knowledge and wisdom. “Jnana” means knowledge or wisdom, especially that which leads to self-realization). The aim of Jnana Kanda is to guide individuals towards spiritual enlightenment and liberation (Moksha) from the cycle of birth and rebirth (Samsara). This is achieved through self-inquiry, meditation, and the cultivation of wisdom and understanding. In fact, it was the excessive ritualism of the time that led to the emergence of Buddhism and Jainism.

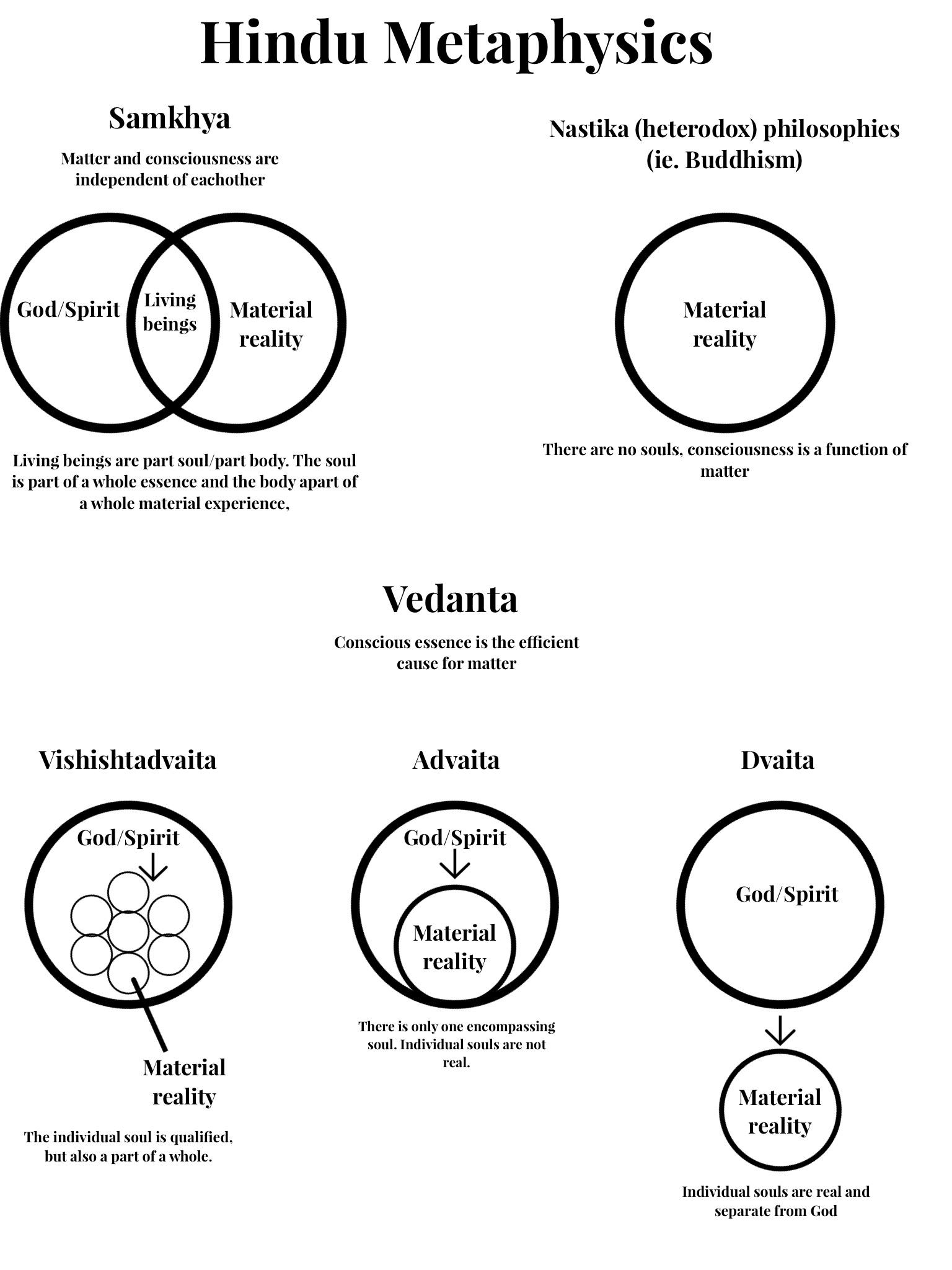

Buddhism, fundamentally, doesn’t believe in the existence of an Atman in the way it’s understood in Hinduism, overlooking the concept of consciousness as the underlying reality outright. Jainism, alternatively, presents a more tangible but limited view of the Atman, defining its physical boundaries of influence.

Other philosophical schools like the Charvakas, steeped in materialism, endorsed a single-life doctrine and equated sensual and physical pleasures with happiness. The Samkhyas, dismissing a supreme deity, focused on nature’s dominance over individual Atman, rather than questioning the substance of it. The Yoga school, although similar to Samkhya, also acknowledged a divine unifying entity. The Mimamsakas, on the other hand, chose to solely embrace the ritualistic aspects of the Vedas, ignoring the knowledge component entirely. Sects like the Shaktas, Shaivas, and Vaishnavas each venerated a singular Vedic deity as the ultimate, excluding others.

Ancient India always maintained an incredibly rich tradition of ontological discourse and, although it promoted a diversity of perspectives, it created a form of cognitive dissonance among those trying to navigate a path for themselves. In this fragmented landscape, as many as 72 distinct schools of thought fought for dominance, leading to turmoil, confusion, superstition, and intellectual darkness.

It was during this time in India’s history that the great sage Shankara was born. He harmonized the various sects under the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta, positing that existence at its core is actually non-dual in nature. He illuminated the essence of the Upanishads, expressing that the ultimate purpose of the Vedas was to bring one to the realization that the Atman and Brahman are one and the same. Shankara acknowledged and gave due recognition to various forms of worship, viewing them as paths catering to diverse spiritual needs, guiding the practitioners towards their form of ultimate perfection.

He was born to a poor Brahmin family in a village named Kaladi in Kerala in the year 788 A.D. Almost immediately, he was known for showing signs of being extremely intelligent for his age. His mind would consistently ponder the wonders of the universe and how things worked around him. It was this voracious appetite for wisdom and knowledge that eventually led him to start his Sannyasa at the humble age of 8. Sannyasis, Rishis, and Brahmins would garb themselves in orange because it represents the sacred flame of the Havan, within which all material desires and pleasures are sacrificed. Taking this oath of selflessness allowed ancient Indian scholars to sincerely dedicate themselves to the pursuit of demystifying the universe.

Shankara would walk the length of India twice as he travelled from village to village challenging countless Rishis and Brahmins on their views. He became notorious for debating scholars from all walks of life as he travelled. At the age of 16, he had fully developed the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta and explained it through his commentaries on the Brahma-sutra, the principal Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita.

It is sometimes difficult to explain what the philosophies themselves propose without first defining the fundamental words these ancient scholars used to describe the universe. Unfortunately, many of these “untranslatable” words have been crudely translated in insufficient ways for many years. In order to rectify this confusion, please keep the definitions of the following words in mind as you look at the diagram below:

Atman ≠ Soul Atma or Atman is a fundamental principle in Indian philosophy and spirituality. The Sanskrit root ‘ata’ means ‘that which is in constant motion’. The Atma is always in movement from one body to the next, a constant flow maintained by the cycle of birth and death. The ultimate pillars of Hinduism come from understanding the difference between the words atma and prakriti. While Prakriti is the aspect of the universe that is always in flux and subject to evolution, the Atma is immutable and remains untouched.

Brhaman ≠ God/Spirit Brahman is quite literally the nature of ultimate reality: the eternal conscious, irreducible, infinite, omnipresent spiritual core of the universe.